One of the big talking points during the 2024 season was Red Bull’s second seat. Let’s be honest—Sergio Perez had a rough year, and eventually, he was replaced by rookie(ish) Liam Lawson. But let’s not sugarcoat it—driving alongside Max Verstappen is one of the toughest gigs in Formula 1. So, what exactly would qualify as a “good” season for Liam?

Dr. Helmut Marko has gone on record saying they expect Lawson to stay within three-tenths of Max’s lap times. According to him, that would be good enough to bring in solid points for the constructors’ championship.

This got me thinking: would three-tenths really cut it? To find out, I ran a simulation of the 2024 season. The twist? I replaced Sergio Perez with a fictional version of Liam Lawson, tweaking his pace to reflect different deltas to Verstappen. We know Sergio’s actual results weren’t enough to keep him in the seat, but would staying within three-tenths have been enough to save “Liam’s” job? Let’s dive into the numbers.

Methodology

I’ll walk you through my methodology step by step. While the concept is simple enough, explaining it in detail can get a bit tricky, so bear with me.

-

Testing different deltas

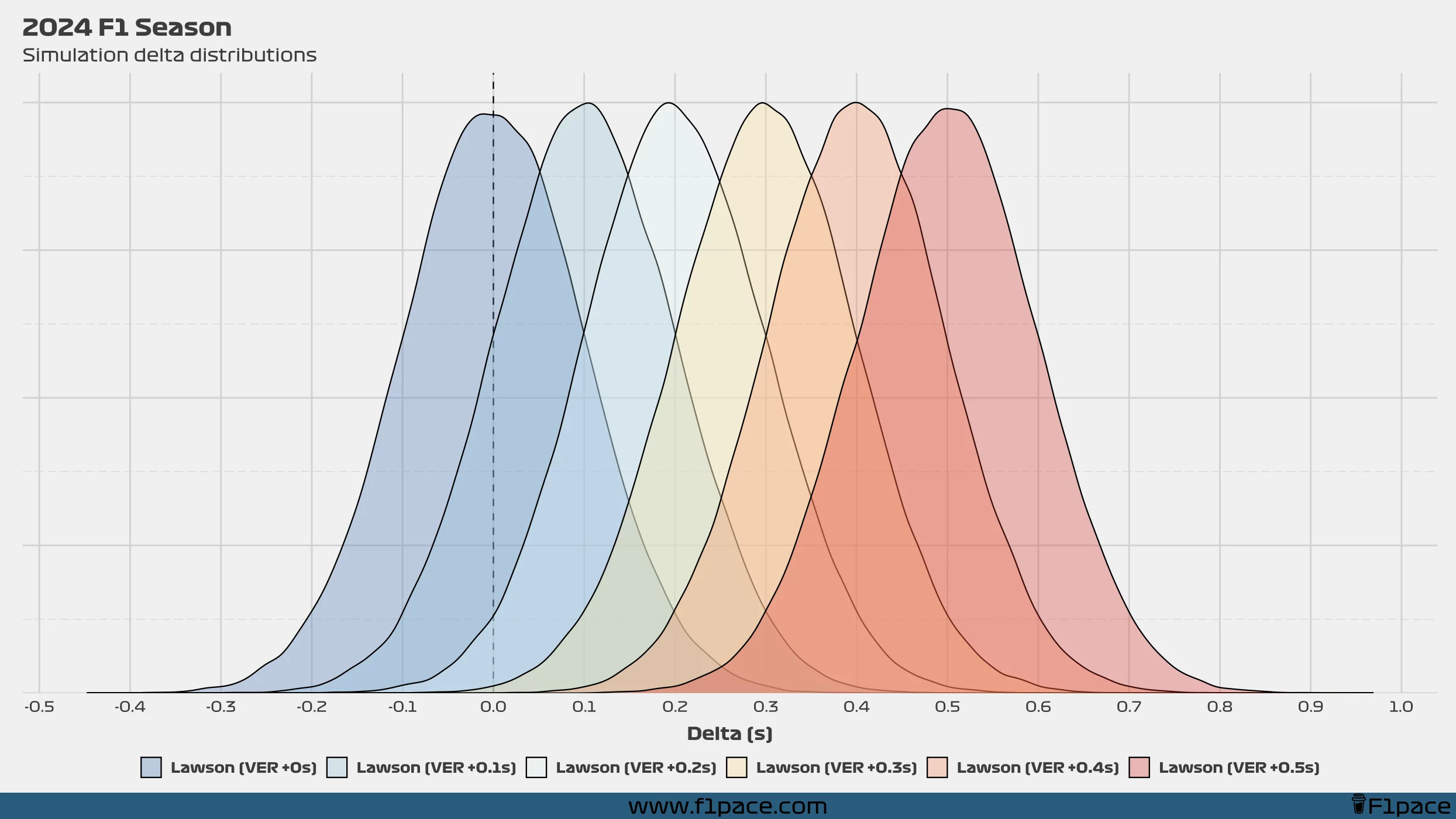

I tested six different average deltas to Max Verstappen in qualifying, ranging from 0 seconds (perfect match to Max) to 0.5 seconds (5 tenths) slower. I tested these in 0.1-second intervals. For example, let’s start with the 0.3-second (3 tenths) simulation. -

Replacing Sergio with a simulated Liam Lawson

I removed Sergio Perez from all the 2024 qualifying sessions and replaced him with a simulated “Liam Lawson.” -

Assigning Liam’s delta

Fake Liam’s delta to Max in each of the 30 qualifying sessions was determined using a normal distribution. For the 0.3s scenario, the mean delta was 0.3 seconds, and the standard deviation was 0.1 seconds. This means most of Liam’s deltas were close to 0.3s but could vary—he might be 0.2s slower in one session, 0.4s in another, or even have more extreme outliers occasionally. -

Adjusting the grid

Based on Liam’s simulated qualifying times, I recalculated all the qualifying positions for each race. The other drivers kept their original qualifying times; only Liam’s times were adjusted. -

Simulating multiple scenarios

I repeated this simulation 1,000 times for each of the six delta scenarios, resulting in a total of six scenarios (from 0 to 0.5 seconds slower, in 0.1-second intervals), each simulated 1,000 times. -

Calculating the results

After running all the simulations, I calculated summary statistics for each scenario to get an average picture of how things played out across all the races.

Summary of Simulated Scenarios

- 0 tenths (+0.0s): Mean delta of 0.0s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between -0.1s and +0.1s). Simulated 1,000 times.

- 1 tenth (+0.1s): Mean delta of 0.1s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between 0.0s and +0.2s). Simulated 1,000 times.

- 2 tenths (+0.2s): Mean delta of 0.2s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between +0.1s and +0.3s). Simulated 1,000 times.

- 3 tenths (+0.3s): Mean delta of 0.3s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between +0.2s and +0.4s). Simulated 1,000 times.

- 4 tenths (+0.4s): Mean delta of 0.4s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between +0.3s and +0.5s). Simulated 1,000 times.

- 5 tenths (+0.5s): Mean delta of 0.5s, standard deviation of 0.1s (most deltas between +0.4s and +0.6s). Simulated 1,000 times.

Below, you can check out the chart showing how the deltas for each race were distributed across the simulations.

I’m leaving a FAQ at the end of the article to try to answer some of the most common questions that you may have about how this analysis was done.

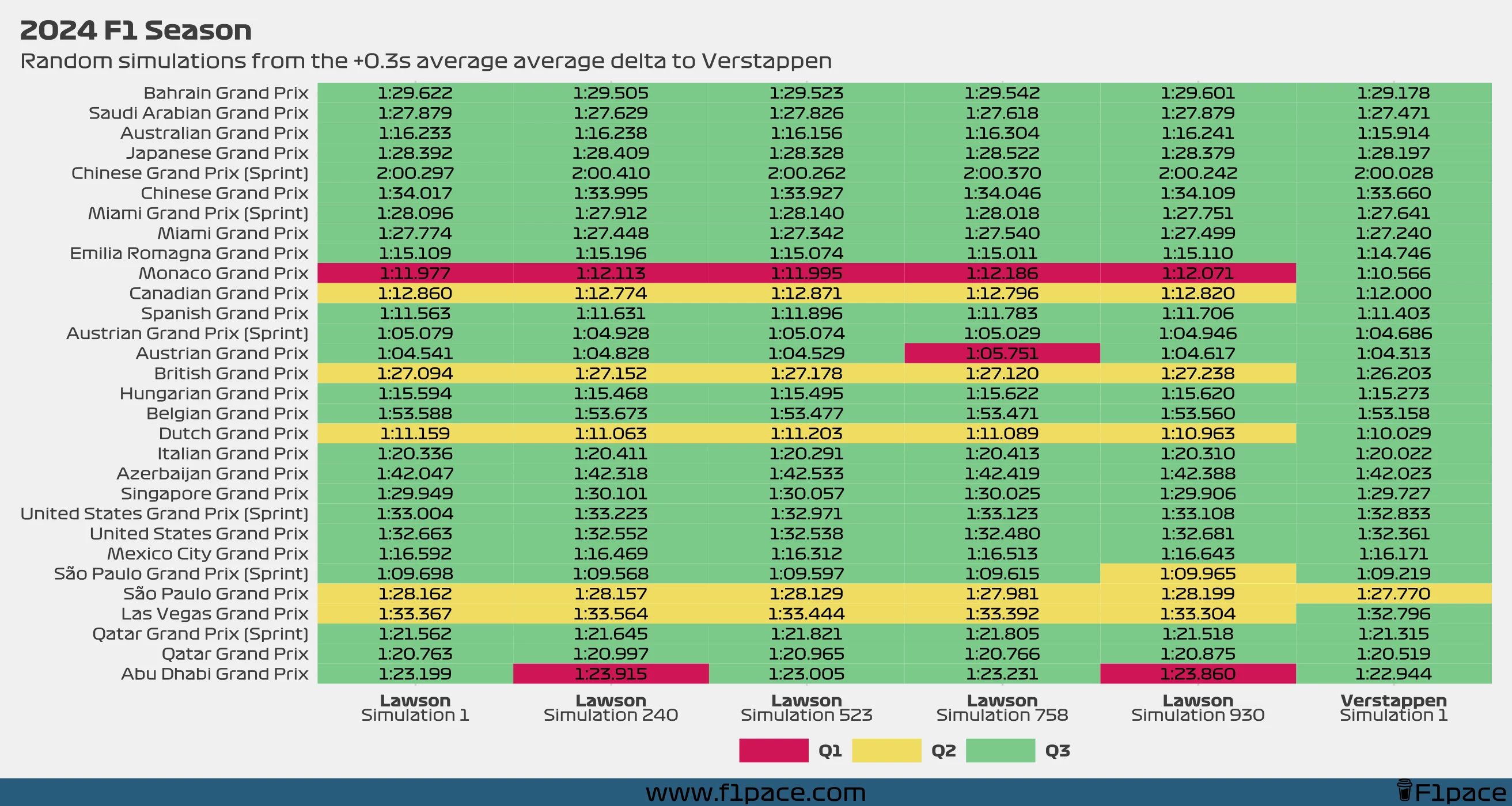

Just as an example of how these simulations looked, check out the chart that shows five random simulations from the 3 tenths average scenario. In all these simulations, the simulated lap times were, on average, 3 tenths slower than Max Verstappen’s, but you can clearly see how the variation in the data plays out.

This variation introduces a wide range of outcomes across the final season results. For instance, being 3 tenths slower on average would’ve cost our simulated Liam a Q1 elimination in Monaco across all five simulations shown. Interestingly, in simulation 758, Liam also had a Q1 elimination—something we don’t see in the rest of the simulations shown.

This kind of variability highlights how even small differences in lap times can have big effects on qualifying results throughout the season.

Impact on Q1, Q2 and Q3 appearances

Now that we know how the simulations were made, let’s dive into the results. How would these deltas (0 to 5 tenths) impact simulated Liam during the 2024 season?

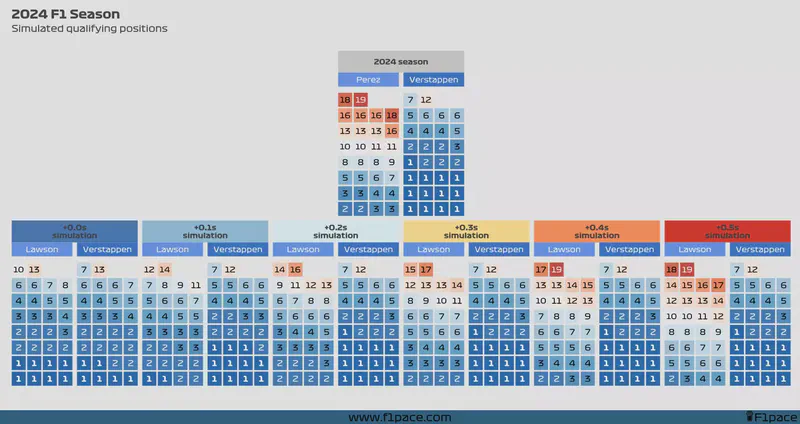

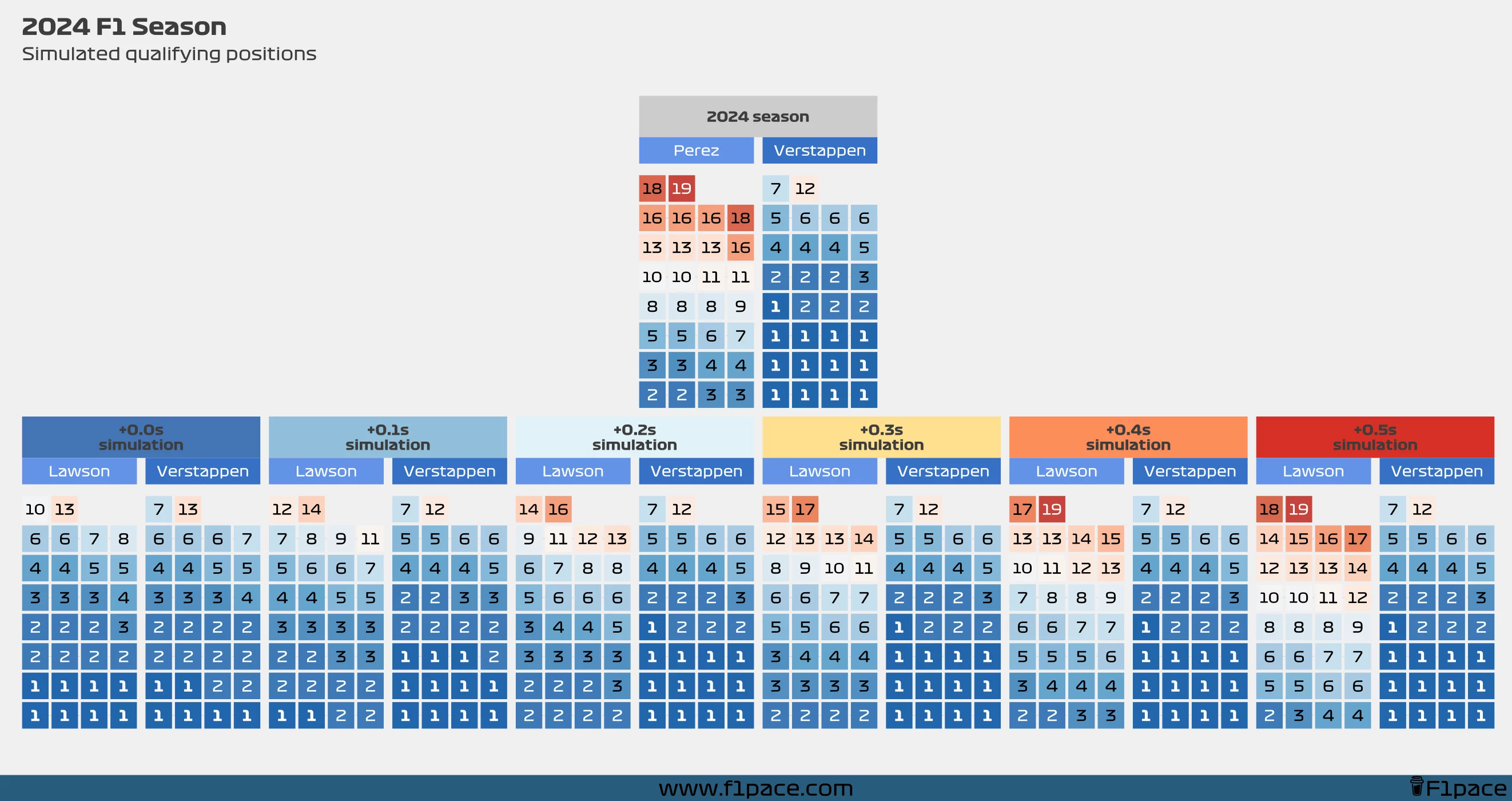

The simulations reveal that with an average delta of 0 tenths to Max, Liam would’ve had 29 Q3 appearances and just one single Q2 elimination. This Q2 elimination was unavoidable since Max himself failed to qualify for Q3 at the São Paulo GP. Interestingly, in this scenario, Liam would’ve outperformed Max in pole positions, with a score of 8-6. This is significant because having a teammate as strong as Max could have potentially cost him the World Drivers’ Championship (WDC) title by splitting critical points.

As the average delta increases, the number of Q1 and Q2 eliminations also grows. At an average delta of 0.1 seconds, the simulations show two additional Q2 eliminations. At 0.2 seconds, we see one more Q2 elimination and the first Q1 elimination.

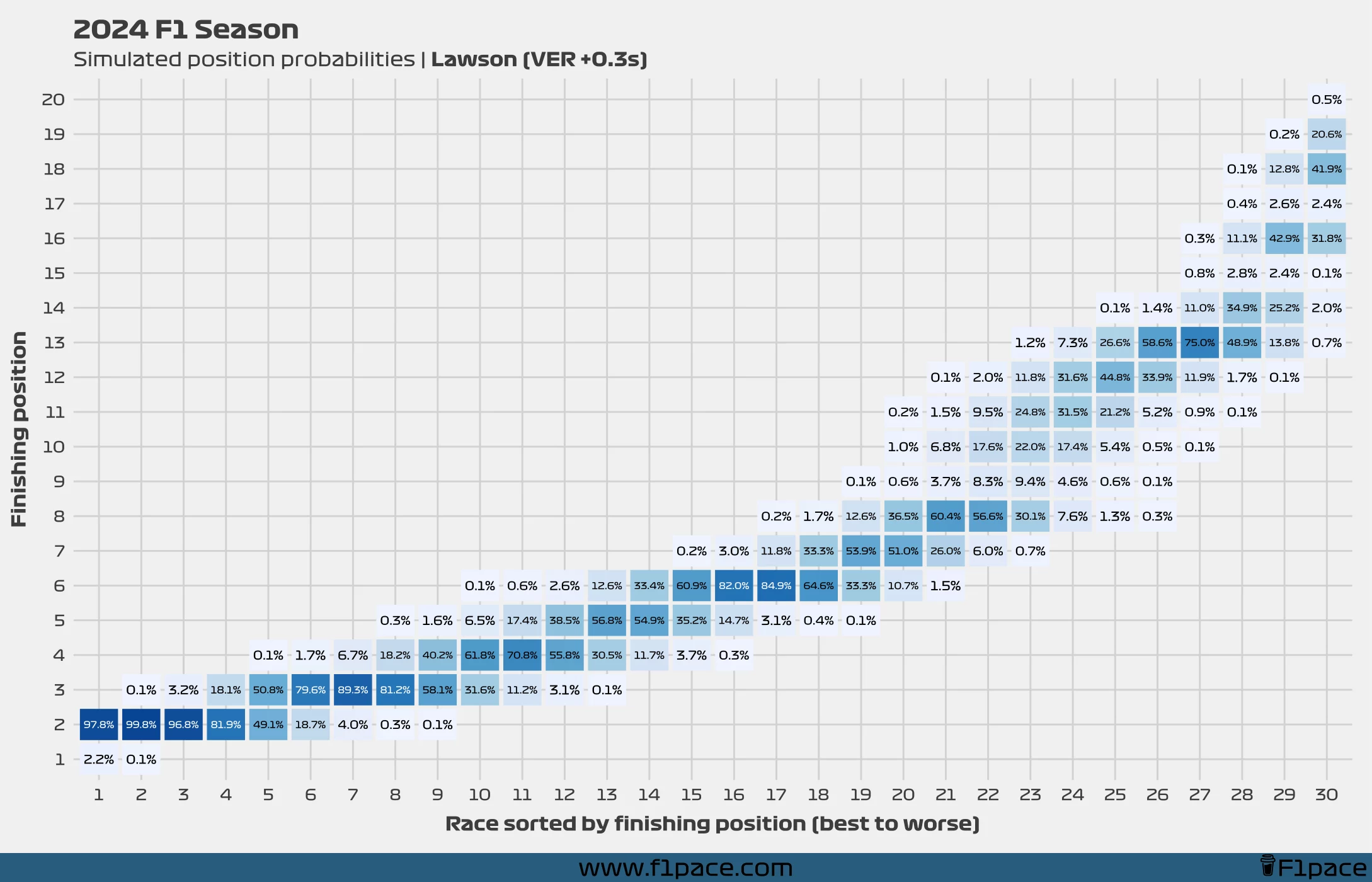

At the expected 0.3 tenths delta, the numbers fall below what you’d expect from a Red Bull driver. The simulations show that an average delta of 0.3 seconds would’ve resulted in six Q2 eliminations and one Q1 elimination for fake Liam. Meanwhile, Verstappen’s season would remain unchanged, with 29 Q3 appearances and 13 pole positions.

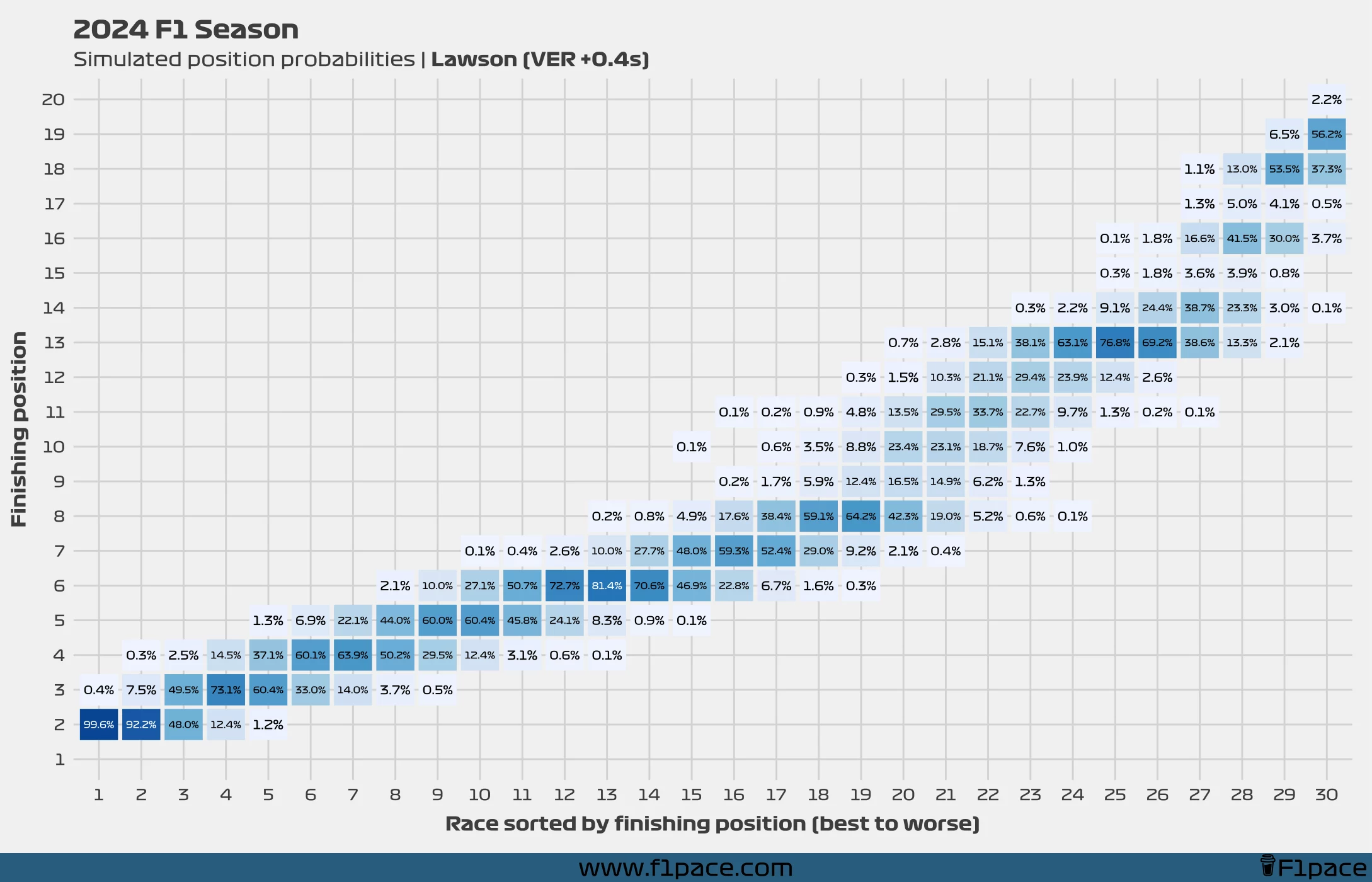

What if things were even worse? At an average delta of 0.4 seconds to Max, Liam would’ve failed to reach Q3 nine times, compared to just once for Verstappen. If we increase the delta to 0.5 seconds, the results become even more dramatic, with eight Q2 and four Q1 eliminations for Liam.

These results highlight how critical even small performance gaps can be when competing at the top level in Formula 1.

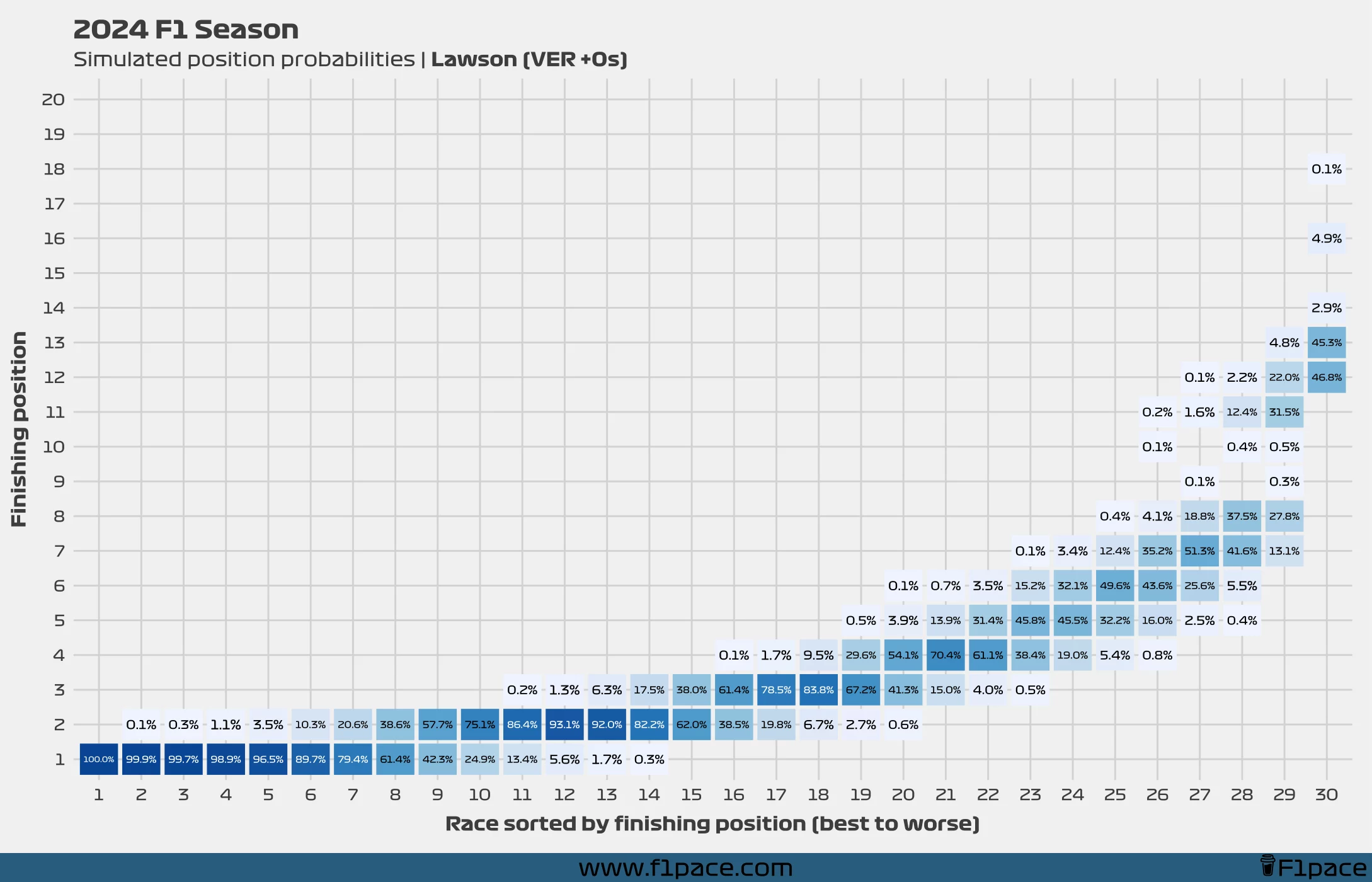

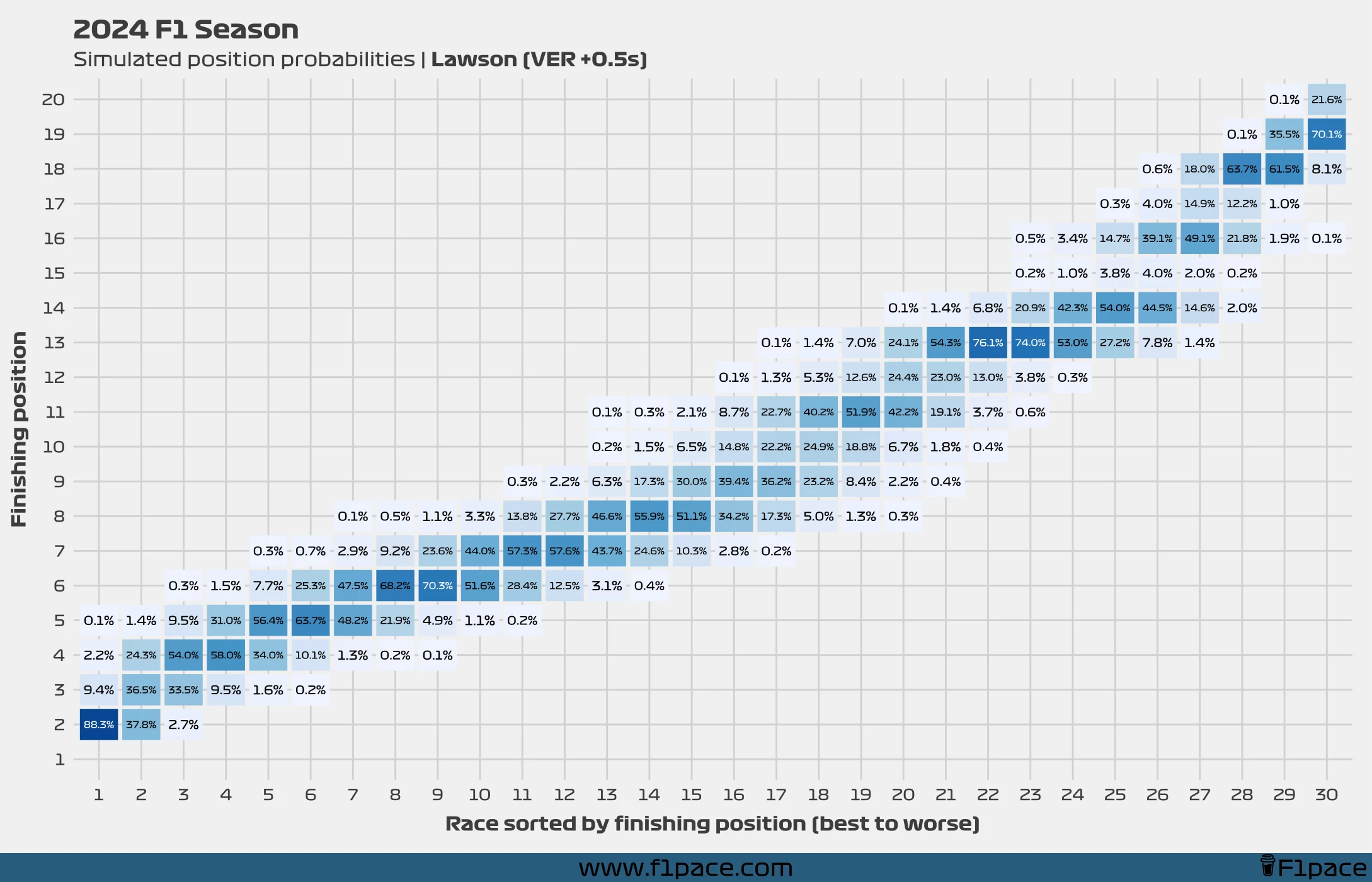

Impact on final position

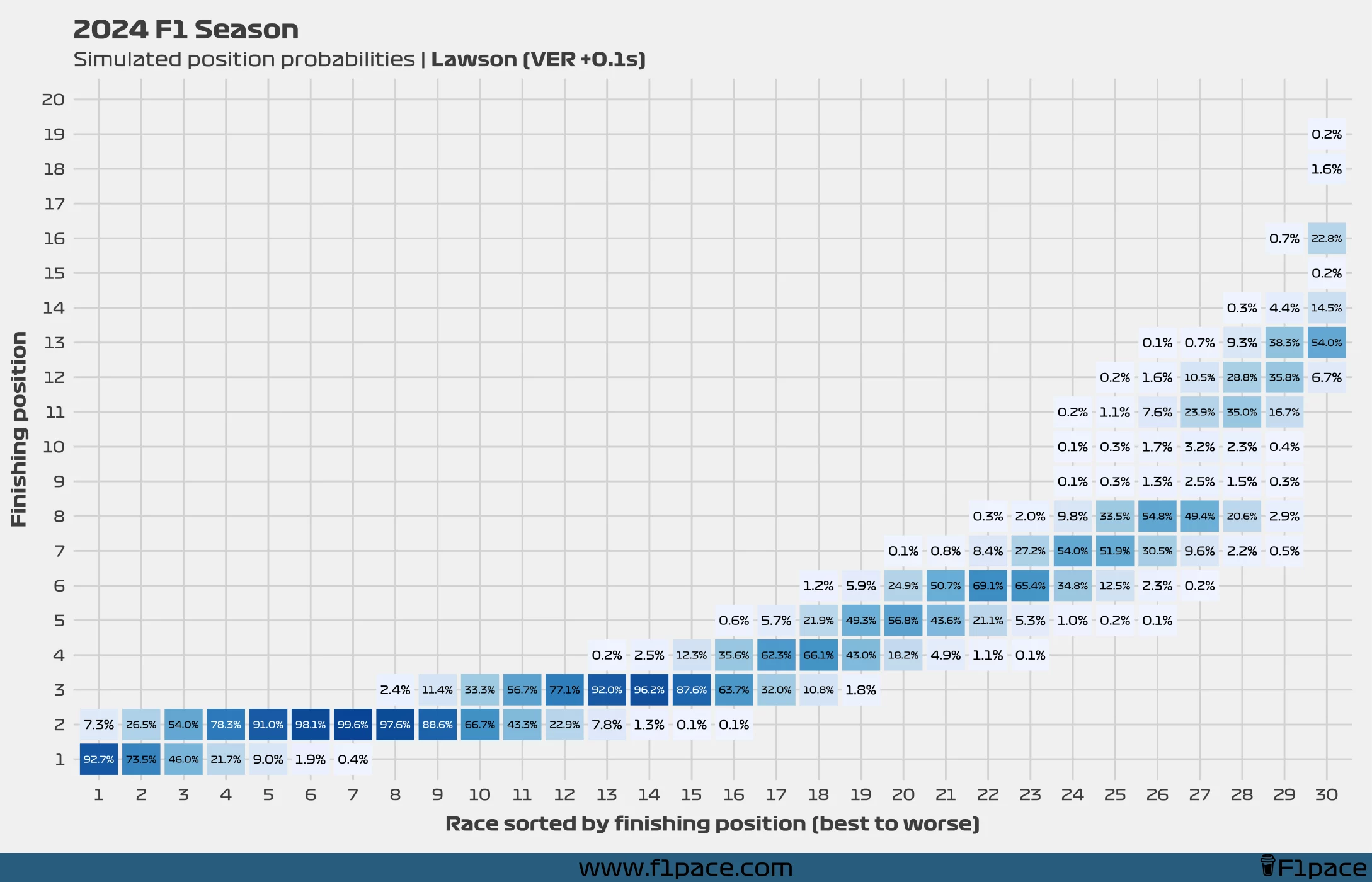

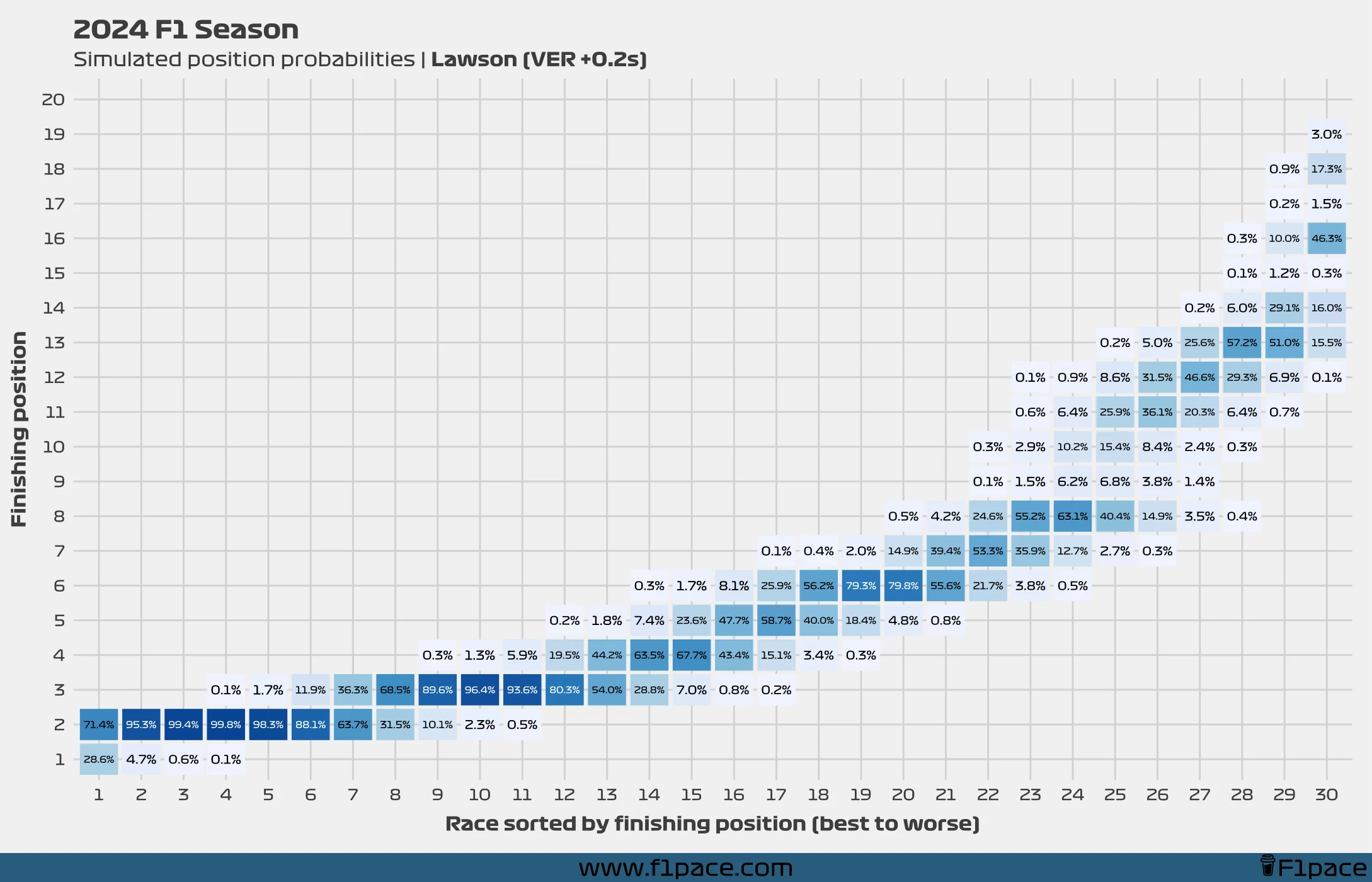

Instead of focusing on quali session appearances, let’s look at the final qualifying positions, which better emphasize how increasing the average delta to Max negatively impacts performance.

Based on the simulations, the only scenarios where you would reasonably expect Liam to achieve a pole position would be with an average delta of 0 or at most 1 tenth to Max. While a higher delta of 2 or even 3 tenths could occasionally result in a pole position, these instances would be anomalies and not the norm.

For example, in the +0.2s simulations, Liam would have started on the front row an average of 7 times (23% of the time). At +0.3s—the benchmark according to Dr. Helmut Marko—Liam would have managed only 5 front-row starts (17% of the time), compared to Max’s 19 front-row starts (63% of the time). As the delta increases to +0.4s and +0.5s, the numbers worsen significantly for Liam.

You can see the full results in the chart, but in my opinion, these numbers wouldn’t relieve the pressure on Verstappen’s teammate. Red Bull expects a consistent and reliable second driver, and these results suggest that even with a 0.3s average delta, Liam’s performance might fall short of expectations.

Best and worse case scenarios

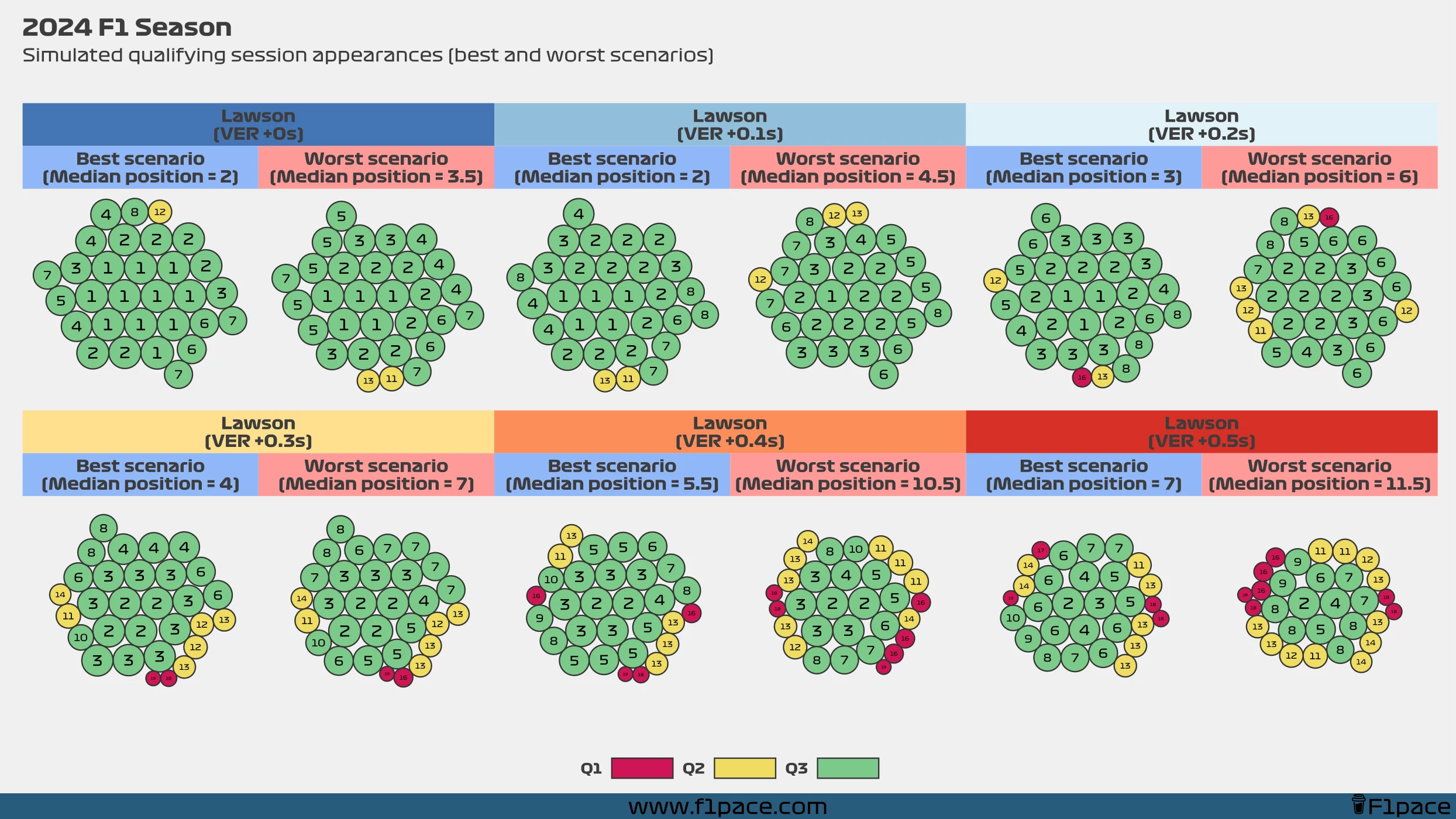

One of the main advantages of running simulations is the ability to examine the variability within each scenario. Previously, we looked at average positions and the number of Q3 or Q2 appearances across the simulations, but the individual simulations often tell a more nuanced story, especially when we focus on specific races where our simulated driver struggled.

Let’s dive into the critical +0.3s scenario. I selected the best simulation (simulation 296) and the worst simulation (simulation 166) in terms of median finishing position, and the differences are striking. In both cases, simulated Liam failed to qualify for Q3 on 8 occasions, but the outcomes within those missed opportunities varied significantly.

In the best-case simulation, Liam qualified in 2nd place four times and in 3rd place nine times, showing a strong performance in the races where he reached Q3. Conversely, in the worst-case simulation, Liam managed only three 2nd-place starts and four 3rd-place starts. These subtle shifts add up—qualifying around 4th place on average might be considered a good season, but qualifying around 7th would undoubtedly create pressure on Liam’s seat at Red Bull.

The variability becomes even more pronounced in the +0.4s scenario. In the best-case simulation (simulation 73), Liam was eliminated 5 times in Q2 and 4 times in Q1. In the worst-case simulation (simulation 15), those numbers jumped to 9 Q2 eliminations and 6 Q1 eliminations, resulting in a total of 15 failures to reach Q3.

This highlights an important point: while the average scenario gives us the most likely outcome, the extremes within each test group reveal how fragile performance perception can be. A few bad results in critical moments can significantly alter how a season is viewed.

This is something that arguably happened to Checo during the 2024 season. His 4 Q1 eliminations in 16th place and 2 Q2 eliminations in 11th place created a poor impression. Had he converted just 2 or 3 of those into more favorable positions, his qualifying stats would have looked much better—perhaps 4 Q1 eliminations instead of 7, and 3 Q2 eliminations instead of 5. While the overall result still might not have been stellar, it could have been enough to strengthen his case to retain his Red Bull seat.

The advantages of running simulations

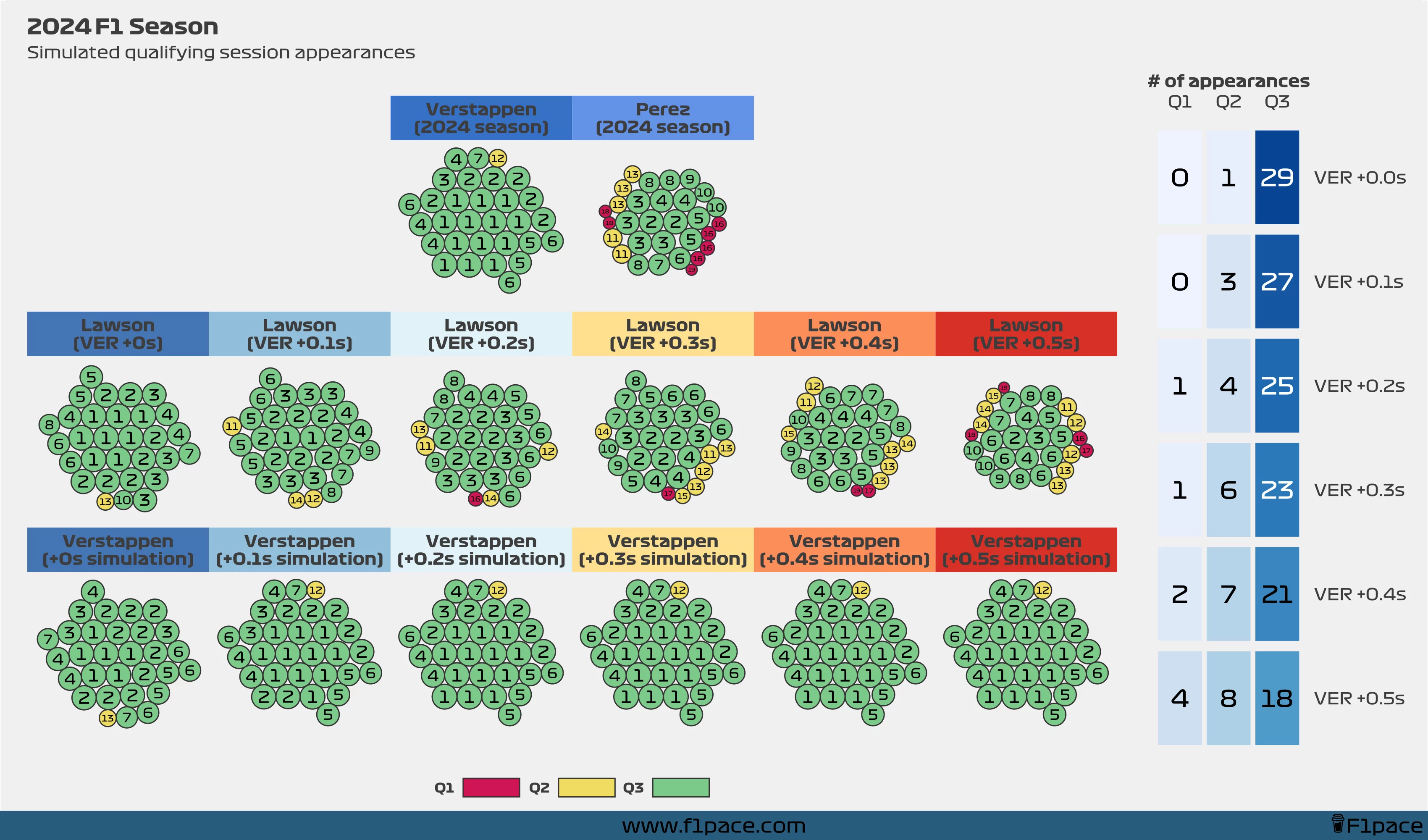

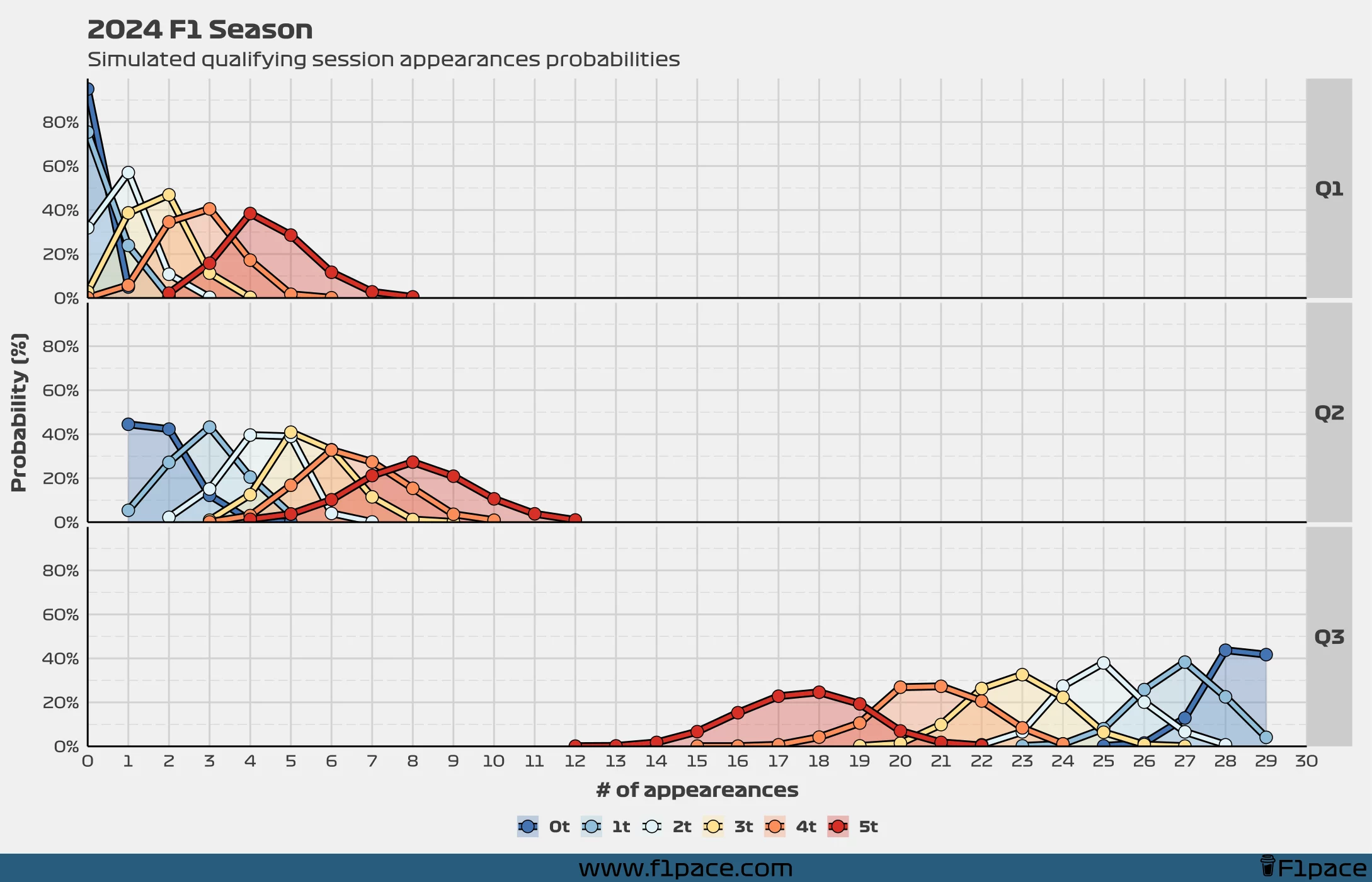

We’ve seen the averages, best and worst outcomes, and Q1, Q2, and Q3 appearances derived from our simulations. However, those numbers aren’t set in stone. Simulations inherently carry variability, meaning that even in our +0.0s delta scenario—where Liam was expected to qualify for Q3 in 29 sessions—it didn’t happen in every simulation.

Take a look at the chart below. Out of our 1,000 +0.0s delta simulations, roughly 40% resulted in Liam qualifying for Q3 28 times instead of 29, and in around 15%, he only made it to Q3 in 27 sessions. This demonstrates the impact of small margins, where a fraction of a second here or there can make a significant difference, including eliminations in Q1 or Q2.

The bottom six charts explore this concept further by focusing on the expected qualifying positions. For example, in the +0.0s delta simulations, Liam averaged 8 pole positions. But as the charts show, this number isn’t definitive. In some simulations, Liam secured as many as 14 pole positions, while in our best-case simulation, he only managed 11.

This highlights how additional simulations could, in theory, reveal even more extreme outcomes—perhaps even Lawson dominating the 2024 season. However, remember that such results would be anomalies, not something you’d realistically expect based on the given parameters.

Conclusion

So there we have it—an analysis of what we could’ve expected from our hypothetical Liam Lawson in 2024 based on different parameters. The results were pretty varied. The +0.0s version of Liam not only matched but beat Max Verstappen, while the +0.3s version would’ve done better than Sergio Perez but still failed to qualify for Q3 on seven occasions.

If the 2024 season is any indication of what 2025 will look like, would three tenths be enough for Liam? Based on my simple analysis, I’d say no. Sure, Lawson would outperform 2024 Sergio, but he’d still be far off Max and rarely fighting for wins or pole positions. I think it’s fair to say most of us don’t expect Liam to match Verstappen, but I doubt fans would be happy with him failing to make Q3 seven times in a season.

I’d argue that the minimum required from Liam would be an average delta of +0.2s to Max. Even then, we might see a few Q2 eliminations (or even Q1 on a bad day), but it would also significantly increase the number of times Liam could fight for a spot on the front row. Is this achievable for him? I’m not entirely sure, but I think failing to hit this target would put him under a lot of pressure during the season.

Final remarks

I hope you enjoyed this article! This simulation-based analysis took me quite a while to put together, as I went back and forth on how to handle the data and decide which charts to include.

I’ve been working on this project for years now, and I always strive to deliver insightful and detailed analysis. I’m not a fan of lazy journalism or quick 10-minute takes that rarely provide accurate or meaningful insights. Hopefully, those of you who visit my site appreciate the quality and effort I put into my content.

I know it’s the off-season, but if you have a moment, I’d really appreciate it if you could share this article. And if you’re able to, consider supporting me financially by clicking the Buy Me a Coffee button—it would mean a lot!

FAQ

- Did you take into consideration the length of the track before adding the delta to “fake Liam?”

- No, the delta was the same regardless of the track. While it is true that sometimes you find bigger gaps on longer tracks, that isn’t always the case. Sometimes teammates are very even on long tracks like Spa, while at times they are separated by many tenths on short tracks like Spielberg or Monaco.

- Since you didn’t correct for track length, is your analysis wrong?

- Yes and no. All analyses are wrong to a certain extent. We do what we can with the data available and with the time at our disposal. Simulations are basically hypothetical scenarios, so even though I didn’t consider track length for this analysis, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the results aren’t valid. They’re not perfect, but they’re still valid.

- Why did you do 1,000 simulations, why not 10,000?

- Time. With our 1,000 simulations for each scenario, we ended up with 6,000 simulations. In total this created a dataframe of over 8 million rows of data. Doing 10,000 simulations per scenario would’ve meant a final total of 60,000 simulations and over 80 million rows of data.